Last week Adrian gave a talk at the Future Makespaces 2nd Symposium organised by the Royal College of Art. His talk was about the less obvious parts of running a makerspace, and here are the slides and his notes (which should be pretty much what he said, but…)

Hello, I’m Adrian McEwen, one of the co-founders of DoES Liverpool. It’s (sort of) a makerspace (and more) in Liverpool.

We’ve been running for over four years now, and I wanted to share some of the non-obvious aspects of that.

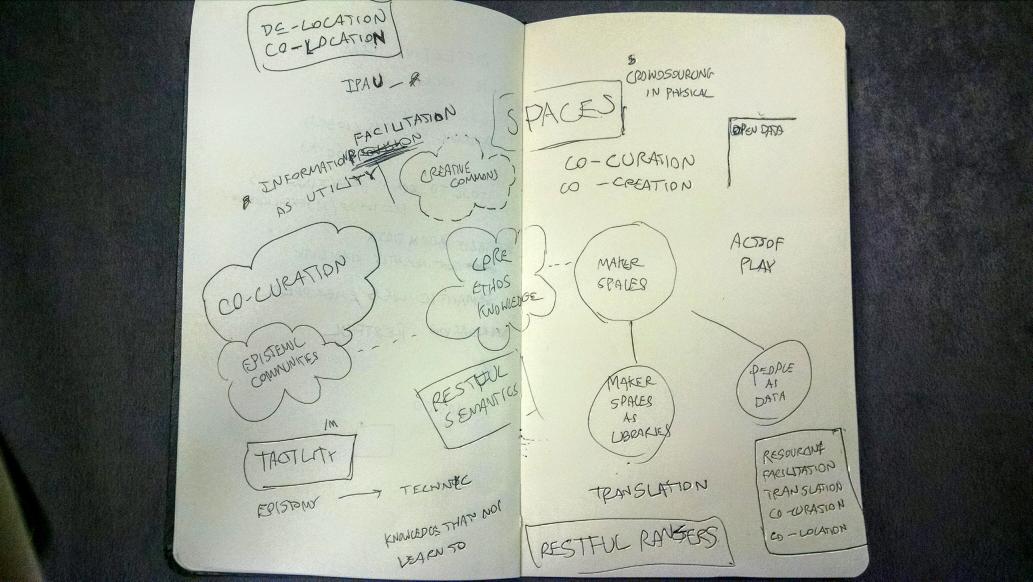

When we started DoES Liverpool we thought about what it was trying to achieve and how it would fit into the rest of the city.

An important part of what we set out to do was to grow and encourage the tech and maker community in the city, and help it prosper through more tech and maker businesses. It was one part software-is-eating-the-world, with another part the workers owning the means of production – initially as software engineers, but increasingly with digital fabrication tools, and a dash of being the change we want to see in the world.

So we were never just a makerspace.

The co-working and office space is just as important as the workshop.

Successful businesses require all sorts of skills, and the more diverse our community, the better the things that will come out of it.

We have artists, engineers, coders, designers, but also copywriters, translators, consultants and charity workers. Freelancers, startups, and remote workers from big corporations.

And we also provide a space for the community to meet.

We knew how hard it was to find space to hold meetups, to get together to share knowledge and just hang out with like-minded people. So part of the space is available for the community to book for free.

I think one of the important aspects is that DoES is run by a bunch of people who don’t really want to run a space. We just want to use the facilities it offers, for our businesses or interests.

As a result, our aim is to minimise the amount of effort required to run it, and one of the ways we do that is by engaging with the “dark matter” surrounding DoES Liverpool.

Wouter Vanstiphout came up with the term, and it was popularised by Dan Hill in his pamphlet “Dark Matter and Trojan Horses”.

It is all the stuff that affects the organisation but that you can’t see or touch. If the matter is the building and the tools, the objects produced and the businesses founded, then the dark matter is the culture of the community, the rules, regulations and policy – and not just in the space, those surrounding the space from the council or the Government.

It could be the way we use cake as currency (it doesn’t have to be homemade, although they’re always the best received), to start things off on a convivial and sharing note.

Or the way we make sure we have good coffee (and buy it from a local independent coffee shop to support them)

Which meant that the coffee machine was the first bit of kit we bought.

It’s the way we bring concepts from software into the physical world. Automating the repeated tasks like the weekly newsletter or marking who has been in on which days…

…or repurposing code issue tracking to let people know what needs doing around the space.

Just as important is what we don’t do.

Despite its name, DoES doesn’t do anything.

The only things that happen are those that the members are committed enough to make happen. And we try not to expand into things that the community could make a living from – we exist to support it, not absorb it.

So we don’t run training courses. That would require trainers, and marketing, and…

It’s much better that members of the community provide that – they can build it as part of their business and then pay for the facilities at DoES to deliver them.

It also lets members of the community experiment with new ways of arranging their work.

For example, a number of the members have young children, and so they’re going to toddler-proof the meeting room so they can run “baby and toddler work day” to let them more easily balance parenthood and freelancing.

And it lets DoES’ specialisms evolve organically. Because I’ve been working with the Internet of Things for years now, there’s a tendency within DoES to connect anything and everything to the Internet, to see if it’s useful.

We joke that if something is left stationary in DoES for too long, it’ll end up connected to the Internet. The doors, the laser-cutters and – naturally – the aforementioned coffee machine.

One of the big things we don’t do is funding. Especially for day-to-day running costs.

We’re funded by the community, for the community, and have been since day one.

Funding begets Outputs, and Outputs beget Criteria. Before you know it you’ll have to exclude most of the people you’d like to help, because they don’t look like the picture you painted in order to get your funding.

We have a completely different filter: Is what you’re doing interesting?

Or if not, are you interested in what others are up to?

And we don’t care if you’re a business or an individual, or how old or young you are.

What’s important is that you Do Epic Sh**.

Starting a business is just a tool to achieve certain outcomes. It could be as useful for you to open source your work and help it spread. Or use the workshop to 3d print yourself a new hand to make your life easier elsewhere.

That said, plenty of people are looking to build businesses around their ideas. You can build one of almost anything with our facilities, and probably 10s or maybe even 100s of something. Once you get beyond that, you tend to want to get someone else to help.

The DoES community is a great distributed knowledge base of suppliers to use and things to watch out for. One person will tell you who they used for PCB assembly, and another will let you know about the place that die-cuts boxes on the dock road. As more people do more projects, so the knowledge grows, but it would be good to speed that process up.

To try to do that, we’ve been doing some work with the Local Enterprise Partnership.

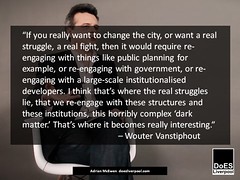

The LEP, and other institutions in the city like the Council, can be tricky to engage with. Especially when you’re harder to work with, like we are. So much of their set up is around funding bids and inward investment that when someone turns up who doesn’t want any of those things, they’re not sure what to do with us.

That’s if they recognise us at all. Because we don’t look like the stuff they’ve been told is “advanced manufacturing”, there’s a tendency to dismiss us as irrelevant. And some times there’s what I call a “mutual lack of respect”, where they think we should court them because they’re the council and important, and I think they should be courting us because we’re actually making a difference and getting on with it regardless of their involvement.

As time goes on, we’re getting harder to ignore, and some of the people working there do get it. One of those is Simon Reid at the LEP.

He’s in charge of the manufacturing sector at the LEP – that’s another problem, we don’t fit neatly into their sectors, as we’re equally manufacturing and digital-and-creative. His challenges for the sector are around skills shortages and keeping the local businesses abreast of emerging technology and possibilities.

So there’s a good match – he knows all the local supply chains and manufacturers, and we’re providing a way to enthuse more people about making and are experimenting with lots of the new technologies.

We’re planning an event to inform local manufacturers about the possibilities that the Internet of Things brings, and have started mapping out what capabilities are around the region. The Future Makespaces levels of study has helped out with that, as it’s provided a good way to frame things.

It’s early days, but hopefully it will be a fruitful relationship.

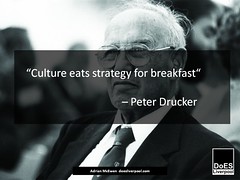

There is more to running a makerspace than the tools you buy or the space that you put them in. If you get the culture right the rest will take care of itself.

And if we engage with the dark matter in the wider context, we have an opportunity to nudge our culture away from consumerism, away from the bankers, and towards a more productive future.

Thank You